This post was originally published on the JSPG blog.

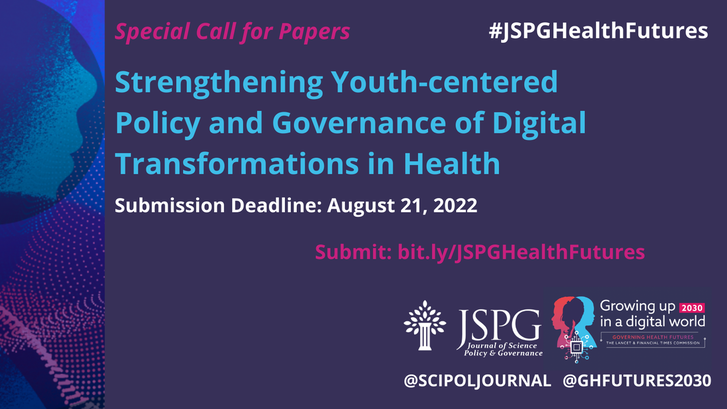

Earlier this year, the Journal of Science Policy & Governance (JSPG) and The Lancet and Financial Times Commission on Governing health futures 2030: Growing up in a digital world (GHFutures2030) launched a call for papers and competition focused on Strengthening Youth-centered Policy and Governance of Digital Transformations in Health.

Asilata Karandikar, Doctoral Student, International Institute of Information Technology Bangalore, Karnataka, India

The special issue and competition seeks to provide young people with agency with respect to digital technologies, and to ensure that digital health governance is co-designed and co-governed for and with youth to drive forward the agenda of achieving health futures for all.

A workshop and two webinars were organized in the lead up to the submission deadline to inspire and help authors with their writing for the call for papers. Below are testimonials of each event by early career participants from around the world. Introduction by Asilata Karandikar.

I was interested in attending this event to gain insight into how we can communicate our science appropriately to non-scientific audiences in order to advance shared goals of improving digital health policy. Often, we are trained as scientists to communicate through talks of field-specific jargon or scientific journals. There is a need for scientists to be involved in the policy process to learn how to effectively communicate to these non-scientific stakeholders. Training in policy writing and communication to these audiences is often lacking in the standard academic training and I attended this event to improve my understanding of science policy paper writing.

– Monique Mills, Ph.D. candidate, The Jackson Laboratory

Takeaways from speakers

Whitney Gray introduced the session on science policy paper writing and focused on the need for youth-centered policy and governance of digital transformation in health. Gray is a part of GHFutures2030, which is leading a call to action to address how the development of the digital world can be leveraged to improve the health and wellbeing of youth. The goal of the project is to identify how technologies like artificial intelligence, can be applied in equitable and affordable ways to universally improve health. To address the role of digital technologies as determinants of health, GHFutures2030 partnered with JSPG on a special issue to identify which policies and what research is needed to utilize these technologies to improve health.

Perhaps, like myself, you may be now wondering how can I, as a scientist, write an impactful policy piece? Rohinton P. Medhora, president of the center of international governance innovation and GHFutures2030 Commissioner, discussed the seven traits that can make for an impactful policy piece. Rohinton Medhora’s overarching guidance is to start the policy writing process by identifying the intended audience and goals to be accomplished with the written piece, which can help create a larger impact.

Two other specific traits that make an impactful policy piece, highlighted by Rohinton Medhora, are the need for proper data visualization and understanding how your work contributes to the field. When communicating the importance of your piece, Rohinton Medhora addresses the need for appropriate data visualization for your intended audience. For example, NASA has used maps from space to increase public awareness of climate change by depicting changing landscapes. This form of data visualization has a larger influence on the general population who can quickly see the effect.

The second highlight of Rohinton Medhora’s discussion, knowing how your work fits into the ecosystem of the field, focuses on how a policy piece alone may not be as impactful as an accumulation of evidence over time. For example, we have known tobacco is harmful, but as evidence accumulates the effects of tobacco have begun to be addressed. This means one policy publication on a topic is not an end. The policy publication on a topic is the starting point of compiling information from resources like think tanks and databases, in addition to disseminating the information to build the ecosystem needed for the policy piece to have an impact.

Overall takeaway

To address how technologies can be applied to improve health, we need a better understanding of what policies are needed. For scientists, this means learning how to effectively write impactful policy pieces. An impactful policy piece can include the following seven characteristics: 1) identify the target audience; 2) understand the intended impact and 3) attributions of your piece in the field; 4) use appropriate data visualization; 5) relate to known concepts of your target audience; 6) see your work as part of the policy ecosystem; and 7) be patient with the field and how your piece may be received. Together these characteristics can help create an effective science policy piece.

Webinar: Addressing the role of digital technologies as determinants of health

Watch the webinar here.

What drew you to attend?

I was intrigued by the description of the event, which was going to discuss how digital transformations have impacted or could impact health-related fields. For example, how can investments in digital health and the training of the rising health workforce help ensure sustainable development as technology and global situations continue to evolve? These topics are not something my research-based PhD often talks about, and I was interested to learn more.

– Jennifer L. Brown JD, PhD Candidat, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Takeaways from speakers

Naomi Lee was the moderator, and began by grounding the conversation, describing how research and policy can interact to produce both practical guidelines and key questions to guide future developments. Digital healthcare technology is rapidly evolving and is having a huge impact on society. What exactly is the impact of this digital transformation on society, and how do we make sure that this technological evolution is as equitable and just as possible? Where does technology support health, and where does technology have the potential to harm health?

The panelists for the conversation were Ilona Kickbusch, Chair of the International Advisory Board for the Global Health Centre and Sandra Cortesi, Director of Youth and Media at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, at Harvard University. Sandra is a psychologist by training, with a very international background. She has always been interested in translating research for decision makers in industry and government to help them create policy, which drew her to this field. Ilona similarly credits her interest in working at the interface of academia and social action as influencing her career path. Ilona distilled the essence of the discussion down to a single (albeit broad) question: How do we change our thinking about health‒ distinct from medicine and the health care system‒ and who do we involve in that change?

A question I myself had after the first few minutes of the webinar turned out to be one of the most frequently asked: Why is there such a focus on young people while conducting this research? Ilona and Sandra both provided parts of the answer. Ilona started with population statistics. Looking at the whole world, the majority of low and middle income countries have populations that are young, and those people access the internet more than older age brackets. Young people also make up a large proportion of the healthcare workforce. It is therefore essential that we listen to feedback from this group. The key message from the research focus groups seemed to be that young people are interested in being empowered to access and understand basic health information.

Sandra added that the ways young people use, or are excluded from using, technology has implications for how it should be developed. Sandra continued to mention that access to the internet and healthcare can also be extremely limited in those same countries referenced by Ilona, creating a barrier to health and wellbeing. For example, reproductive healthcare information or access to information about the latest infectious disease outbreak can be constrained by multiple factors that should be considered when thinking of future technology. This is called the digital divide, and references the gap between those who have access to digital skills, technology, and information, and those who do not.

Digital determinants of health, then, are related to the digital divide, and include: who gets information, who can make health appointments, who can see disinformation, who has the power to express their views within their political system, and who can use leisure time to make social connections online. Sandra provided some examples of problems that must be considered by governments that are looking to invest in technological infrastructure. If a person doesn’t have some basic general literacy, it might be difficult to develop health literacy or technology skills, which implicates the education system as a key stakeholder. Likewise, if the technology is too expensive, the people who need it most might not be able to afford it, or might not have access to the internet or to electricity to use the device. Thus, technology itself is just one part of the issue. As Sandra eloquently stated, providing physical infrastructure is not enough without social, cultural and political pieces to ensure that tech is used to empower and not further isolate groups of people from health information.

There were many great questions posed to the panelists, but one I’m sure many of us had was “How can students contribute to this effort and support better health innovation?” The answer was multi-faceted, and since context is important, the best course of action might differ depending on individual situations. Generally, panelists agreed that finding like-minded people to investigate gaps, identifying and contacting allies and key stakeholders, building and mobilizing communities, and translating findings for the public, are all options.

Overall takeaway

Digital divides which can impact access to digital health information include: (1) access to technology; (2) the skill to navigate and understand what is presented; and (3) who has the resources to engage with technology, in terms of time, funding and support. To overcome these digital divides and make future health technologies more equitable, we need multiple stakeholder involvement, and creative thinking to produce solutions. Technology is connected to so many other aspects of life, so while important, alone it is not sufficient to create beneficial change.

Webinar: Governing health data to increase its public value and foster trust

Watch the webinar here.

What drew you to attend?

In the COVID age, health data and virtual health appointments are more prevalent than ever. Large datasets on entire populations now exist, but there are few parameters on who and how this data can be used, and who benefits from access to this data. I was drawn to attend this webinar to understand more about the ethical, moral, and practical implications of these large datasets, and how we can responsibly use these data sets to further human health.

– Sarah Ackenhusen, PhD Candidate, University of Michigan

Takeaways from speakers

The panel was moderated by Shalin Jyotishi, a senior analyst with Education & Labor at New America. He introduced the call of submissions through identifying the importance of youth and early career perspectives in digital health.

Barbara Prainsack, the head of the political science department at the University of Vienna, was the first to be introduced. She described the concept of “data solidarity”, a term with which I was unfamiliar, defined as the attempt to increase collective solutions rather than increased privatization of individual data. Barbara Prainsack, along with others on the panel, discussed the importance of increasing both the health and monetary public value of data, while improving harm mitigation mechanisms. This balance in allowing data privatization from individuals, while also prioritizing structures that help individuals allow use of their data, would allow for the greatest public value, especially when directing the value gained from the public health data back to the people the data was produced from. She identified how health data can specifically improve people’s lives as an interesting class of topics to write on in this submission cycle, along with what currently prevents the use of the data in this way.

Yawri Carr was next to be introduced, a master’s candidate in responsibility in science, engineering and technology at TU Munchen. Her expertise brought the youth perspective into the conversation, and she was excited about the inclusion and empowerment of youth in bridging innovation and governance. Yawri identified the importance of the youth perspective in this conversation as youth have only lived in the digital age, while also highlighting that legislators and those leading these conversations need to reach out to youth more in spaces in which they are most familiar. For example, she identified that the Governing Health commission has a Facebook page for engaging with younger generations. One way she highlighted to identify a topic for this submission cycle is to identify what worries authors on what government or companies are currently doing.

Andrzej Rys brought a governmental perspective as the next panelist. He is currently the director of health systems, medical products, and innovation at DG SANTE, as well as a Global Health Futures 2030 (GHFutures2030) Commissioner. His comments on this panel mostly focused on his role as a commission and digital health regulator in Europe, identifying the importance of explaining regulations to the public. Much of the trust in the government has been lost in recent years, and this impacts human health. The GHFutures2030 is looking to combat this distrust and make a recommendation for a public health architecture, specifically identifying the differences between our analog and digital world, and focusing on human rights, equity, democracy and solidarity principles. They highlight public value, similar to Dr. Prainsack’s comments, as the most important metric, striking a balance between the public and private sectors. When asked about which topics could be interesting to include in this issue, Dr. Rys identified topics surrounding new digital products increasing access to human health: how much are these products aiding human health and which ways are they harming it?

Our final panelist was Marwa Azelmat, a digital rights expert with RNW Media, who focuses on entrenched systems of inequalities in digital rights. She also highlighted the importance of public value, especially in relation to structurally marginalized communities. These marginalized communities were discussed not only along traditional racial and gender based lines, but also in the drastic differences in internet access across the world. One unique perspective she provided was in the characterization of all youth being “plugged in” to the internet—identifying that many communities of young people are still searching for affordable internet. As well as emphasizing the importance of intersectionality in this discussion, Marwa discussed the difficulties in increasing public value, including the governing of big tech, combatting disinformation campaigns, and the growing wage gap affected by technological advancement. In addition, in concert with the discussion of disinformation, she focused on the loss of civic space as our world moves online—that our online regulations (self- and industry-made) results in a surveillance state that often shuts down the voices of marginalized communities. This conversation led to her recommendation for a topic for submission: the use of surveillance practices and algorithmic discrimination by companies for profit.

Overall takeaway

Each speaker emphasized the importance of public value in making decisions surrounding the governance of public health data, as well as the importance of including youth perspectives in decisions surrounding governance. The careful re-establishment of trust in governance through education and data-ownership, along with responsibly managed public data, were all deemed essential in this discussion. The panel also emphasized governance that focuses on incentive structures that aid public health and limits harms, while allowing for innovation and privacy. Overall, the speakers did a wonderful job at comprehensively addressing this issue, and I would highly recommend giving it a watch before finalizing your submission for this month’s call!

Closing

Overall, the events emphasized strengthening youth-centered policy and governance of digital transformations in health. In these events, speakers highlighted key challenges to leveraging the diverse opportunities that digital health provides, reviewed the determinants of digital health and showed how a clear understanding of their impacts can strengthen digital transformations in health. Further, the speakers emphasized the importance of establishing public trust through transparency and adequate governance that allows for digital security, while maximizing innovation. The workshop was phenomenal and the webinar sessions were enlightening, with an opportunity to discuss a range of issues and proffer plausible solutions for better youth engagement and governance of digital transformation relevant to stimulating youth interest and gaining traction for digital innovation and transformation. Submit your ideas to this special issue of JSPG! Closing by Chidinma Oli.

Post compiled and edited by Adriana Bankston.

The Journal of Science Policy & Governance is a non-profit organization based in the United States and an internationally recognized, open-access, peer-reviewed publication dedicated to elevating students, post-docs, policy fellows and young scholars in science, technology and innovation policy and governance debate worldwide.

-

This author does not have any more posts.