Strategy and Structure

Created in 2019, the Commission published its final report and recommendations in 2021, after over two years of independant internal deliberation and input from several external stakeholders in an innovative format.

Meet the Co-Chairs and Commissioners

Co-Chairs and Commissioners represent a wide range of sectors, expertise, and backgrounds. By collaborating and contributing their guidance, inputs, and ideas on matters related to the Commission between 2019-2021, they played a key role in shaping the Commission’s final report.

Co-Chair

Dr Anurag Agrawal

Dean, BioSciences and Health Research, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University

Co-Chair

Professor Ilona Kickbusch

DTH-Lab Director, Senior Distinguised Fellow, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies

Commissioner

Dr Micheal Adelhardt

Head of Competence Centre Health and Social Protection, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

Commissioner

Professor Ran Balicer

Founding Director, Clalit Research Institute; Chief Innovation Officer, Clalit Health Services, Israel

Meet the Secretariat

Partners

Frequently Asked Questions

About the GHFutures2030 Commission

The Lancet and Financial Times Commission on Governing health futures 2030: Growing up in a digital world (referred to as ‘GHFutures2030’ or ‘the Commission’ for short) is the first joint Commission of the The Lancet and Financial Times. It is also the first Lancet Commission on the multisectoral topic of digital health and its impact on children and young people.

The Commission explored the convergence of digital health, artificial intelligence (AI), and other frontier technologies for health with universal health coverage (UHC), with special consideration for young people and those living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). By partnering with the Financial Times, this Commission was able to engage with a wider group of stakeholders, including commercial and private sector actors, without compromising the independence of the report.

As well as its thematic focus, GHFutures2030 is unique for the inclusive way in which it worked with children and youth (learn more in the response to question 5 below).

Finally, the Commission’s work was timely. The COVID-19 pandemic shone a light on—and raised the political profile of—many issues the Commission was already aiming to tackle, further highlighting the timely relevance and importance of digital transformations in all areas of life including health and wellbeing.

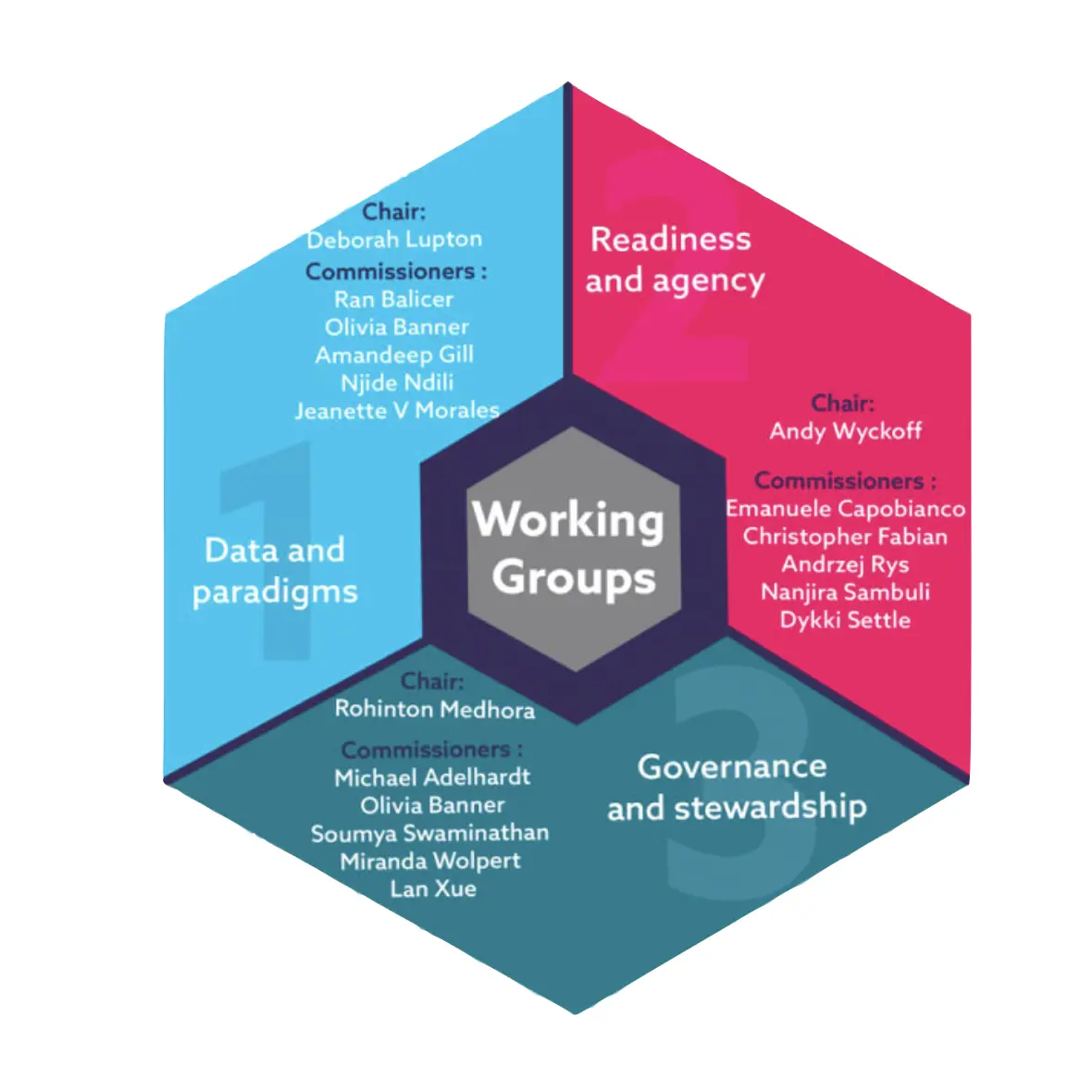

The Commission comprises two Co-chairs, Professor Ilona Kickbusch and Dr Anurag Agrawal, and seventeen Commissioners representing a wide range of sectors, expertise, and backgrounds. Commissioners serve in an independent capacity and comply with the Lancet’s conflict of interest policy.

The Commission is supported by a Secretariat hosted by the Global Health Centre at the Graduate Institute in Geneva. The Secretariat supports Commissioners with research, writing, and logistical organisation.

Over the past two years, the Commission’s work has become increasingly visible through online events and policy dialogues, social media activities, and targeted stakeholder engagement.

The Commission:

- Brought together independent Commissioners from a range of sectors, disciplines, and backgrounds for four meetings between October 2019 and February 2021 to develop its report. Between meetings, Commissioners divided into working groups to dive into topic areas.

- Cooperates with partners to organise dialogues with key stakeholders, including the private sector and youth organisations.

- Supports ongoing digital conversations with youth in order to take their views into account.

- Collaborates with international and UN organisations to establish links with other digital health and AI initiatives, making full use of global, regional, and national events to debate and present the Commission’s findings.

The Commission is funded by Fondation Botnar, The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), and The Wellcome Trust. Two additional grants were received including the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation to further develop youth engagement in the Commission’s report and a grant from GIZ, the German Agency for International Cooperation, to further research approaches to digital health in ten countries with the young populations. The Commission received in-kind contributions from the co-sponsor of the U-Report survey, UNICEF’s Office of Innovation, and partnered with several institutions on particular thematic areas of interest. The funding goes to the Secretariat of the Commission, which is housed at the Global Health Centre at the Graduate Institute in Geneva.

The Lancet does not receive any direct funding for this work.

The Financial Times were contracted by the Commission Secretariat to provide outreach and communication support to the Commission. The Financial Times provides a microsite for both outreach and communication and has arranged a number of convenings for figures in the business community, who would not be able to take part in the Commission due to conflicts of interest. These convenings served to gather information that was shared with the Commission who subsequently determined as to the use for the work of the Commission.

The Co-Chairs and Commissioners advocated for a holistic and strategic approach to engaging youth in the Commission’s work. The Commission established a Youth Team within its Secretariat which facilitated open dialogues to hear the concerns and proposed solutions from youth on the future health governance they want. These discussions resulted in the co-creation of a Youth Statement and Call for Action to complement the Commission report. A version of the Commission’s report has also been created for older children and youth.

The Commission also sought to better understand the experiences and views of children and youth growing up in a digital world through focus groups, interviews, and a global survey of more than 23,000 young people. This research informed the development of the Commission’s typology of digital childhoods which illustrates the diversity of young people’s lived experiences and reinforces the importance of involving young people from different backgrounds in digital health governance. Youth also played a significant role in generating recommendations for strengthening future governance, such as co-designing the proposed framework for assessing digital health readiness.

About the Commission’s report

The scope of this Commission goes beyond a narrow technical view of digital health applications and health data use, which represent only partial components of how digital transformations affect health and wellbeing, now and in the future. The Commission’s report looks at the broader societal and governance questions that emerge at the interface of digital and health transformations.

Weak governance of digital transformations has undermined the potential for digital technologies to be used for the improvement of people’s health and wellbeing. Furthermore, weak governance has led to uneven effects of digital transformations globally, endangering democracy, limiting the agency of patients and communities, increasing health inequities, eroding trust, and compromising human rights, including in the field of health. Because of the fast-paced nature of digital transformations, existing governance frameworks have tended to be reactive to innovations rather than proactive in anticipating future governance questions.

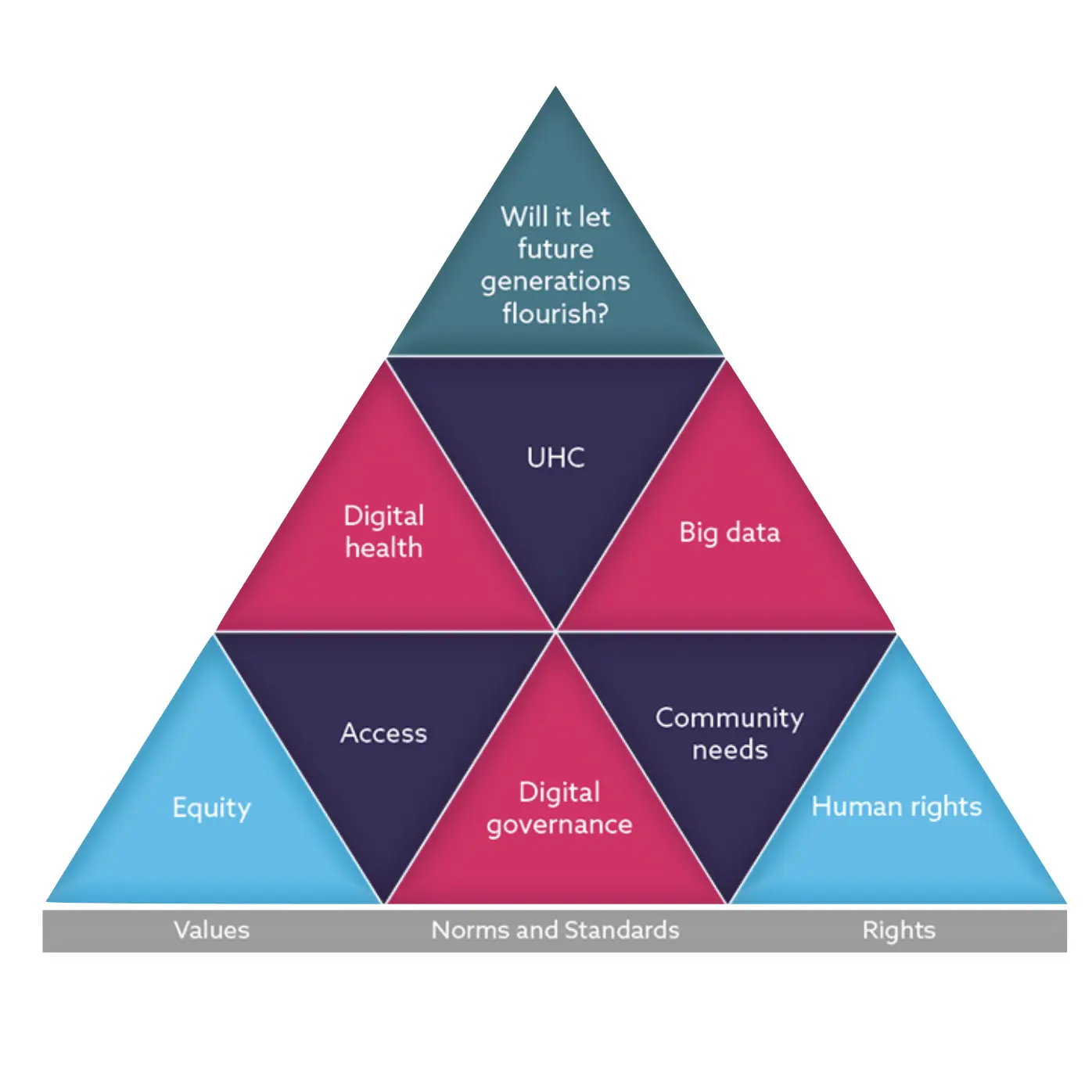

As health emerges as a key driver of innovation and a business frontier for major technology companies and platforms all around the world, the Commission argues that an anticipatory, value-based governance framework based on Health for All values is an urgent requirement if we want to reap the positive potentials of the interface between UHC and digital technologies.

The Commission created a conceptual framework for its report that situates health futures at the interface of digital transformations and the other transformations affecting health, public health, and health systems. Particular attention was given to the implications that such transformations have for children and young people.

The Commission introduced processes of digital transformations that influence health and qualified them as a new determinant of health and wellbeing (see question 11 below). It discussed the required transformations of UHC in a digital age, with focus on the specific conditions, and approaches under which digital solutions can be used by different actors to strengthen public health and expand the quality, affordability, and accessibility of health services.

The Commission’s report describes the diversified experiences and challenges for children and young people growing up in a digital world, and discusses the importance of putting their views, skills, and needs at the centre of a digitally transformed UHC.

The report outlines the foundational entry points of a value-based framework that should guide governments and societies in preparing for, and governing, digital transformations to benefit health and wellbeing.

Viewing digital transformations of health through the lens of UHC, the Commission found that countries’ approaches to digital health governance were lacking in five areas:

- Most countries’ digital health strategies are not focused on maximising the public value of digital health and data to tackle global health challenges and improve health for all.

- Approaches to digital transformations in health and other areas are not sufficiently grounded in key principles—such as solidarity, human rights, equity, and inclusion which could help to increase the public value of digital health and prevent technology and data being used in harmful ways.

- The views and needs of young people are almost never prioritised in digital health strategies and young people are not adequately involved in policy or technology development.

- Governments are not using their full powers to control the actions of technology companies so that they promote health, wellbeing, and human rights—especially for young people.

- Despite the global nature of the internet and digital transformations, governments are slow to cooperate with other countries in agreeing common global governance frameworks for digital health and health data.

The Commission proposes four areas for strengthening governance at the intersection of digital and health transformations. The Commission’s recommendations call for urgent action be taken at subnational, national, and international levels to reduce power asymmetries and create public value.

- Decision-makers, health professionals and researchers should not only consider, but address, digital technologies as increasingly important determinants of health;

- A whole-of-society efforts is required to build a governance architecture that creates trust in digital health by enfranchising patients and vulnerable groups, ensuring health and digital rights, and regulating powerful players in the digital health ecosystem;

- A new approach to the collection and use of health data based on the concept of data solidarity is needed, particularly with the aim of simultaneously protecting individual rights, promoting the public good potential of such data, and building a culture of data justice and equity;

- Decision-makers should invest in the enablers of digitally-transformed health systems, a task that will require strong country ownership of digital health strategies and clear investment roadmaps that help prioritise those technologies that are most needed at different levels of digital health maturity.

The Commission’s recommendations lay out actions that various actors can take to create more equitable health futures.

- For academics and medical practitioners, the report outlines areas and key tensions for future research and directions for practice.

- For policy makers and governments, the report presents novel concrete steps and concepts to consider when governing both digital health and the indirect effects of digital transformations on health.

- For industry, the report summarises existing thought in the digital health space, and provides recommendations for private sector engagement that can work towards positively influencing health outcomes.

- For communities and civil society, the report’s findings and recommendations can be a resource for advocacy and accountability efforts with governments and digital health providers.

The youth edition of the Commission’s report (to be published in December 2021) includes ideas for how young people can be agents of change for better health futures. The GHFutures2030 Youth Strategy, also outlines ways in which the Commission plans to further engage with young people after the report launch.

The Commission launched the GHFutures2030 Youth Network as a platform to co-create and co-lead future research, advocacy, and dissemination of the report. The Network will bring together young people under the age of 30 invested in the health and wellbeing of youth and the future of health governance that is being shaped today. The aims of the Network are to build a movement dedicated to digital health governance inspired by the needs of children and young people, generating dialogues, events, and actions that are co-designed and co-governed for and with youth.

Issues covered by the GHFutures2030 report

UHC means that all people have access to the health services they need, when and where they need them, without financial hardship. It includes the full range of essential health services, from health promotion to prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care. Translating the definition of UHC to practice takes various forms. Historically, UHC has focused on health systems. However, reflective of the multisectoral determinants of health, the accomplishment of UHC has recently been broadened to include other services that may (in)directly influence health beyond the health system itself. Reflecting on how digital transformations influence health, UHC is fundamental to capturing the indirect variables of the digital determinants of health (see question 11 below).

In its report, the Commission argues that traditional notions of UHC do not sufficiently capture the extent to which digital transformations are changing our understanding of health and wellbeing, and the means through which public health goals can be achieved. Reimagining public health and UHC in the light of digital transformations means rethinking the breadth of health services that are offered in health systems and included in the publicly financed UHC package, to better reflect those new dimensions of health and wellbeing that are directly dependent on digital technologies and their role as new determinants of health.

Digital transformations are the multiple processes by which digital technologies and data collection are integrated into all areas of everyday life, including health, and the resulting changes that are brought about as a result.

All health futures will be shaped by digital transformations and will consequently bring about major societal changes. However, digital transformations in health and health care are being pushed forward at an increasingly accelerated pace, often without concern for their public purpose or their impacts on health equity and human rights. As such, digital transformations in health are changing conventional understandings of the health economy as well as the challenges and opportunities facing the governance of such transformations. Moreover, the pace of innovation fuelled by digital transformations has intensified the need to address structural and systemic power imbalances and equity concerns that arise with this new digital health economy.

The rapid pace of digital transformations presents many opportunities and risks for people’s health and wellbeing, often amplified by governments’ inability to keep up with new innovations.

Opportunities of digital transformations include direct and indirect effects on health and health systems. Direct effects on health include increased access to health care information and practitioners via digital technologies, as well as an overall increased efficiency in receiving health and care. Direct effects on the health system include more organised and timely health systems management through technologies such as electronic medical records. Indirect effects on health through digital transformations may include increased energy and internet connectivity, and wider access to education and increased literacy, all effects that can increase income. Indirect effects on the health system through digital transformations may include energy capacity and internet connectivity for formerly unavailable medical technologies and the use of digitalised health data for public health purposes. Beyond the health system, digital transformations can also allow more people to share their perspectives with policymakers on health and related issues.

However, the benefits of digital transformations are not equally shared. This creates what is often termed the digital divide, which can work to deepen divides in health equity. Because of gaps in governance amongst other variables, practices of data extraction and surveillance are going unchecked. Whilst digital health companies are providing immediate health services, they may later work to strengthen systems of inequity due to capitalisation of users’ data; some have termed these practices as data colonialism. When digital transformations are driven by the private sector and left unaddressed by governance, this often creates further harm upon marginalised and oppressed populations; for example, in the case of ‘AI bias’ in health care and other domains.

Digital health technologies are helping to expand coverage and quality of healthcare for young people from conception to early adulthood, including in contexts where health systems are weak and where large populations of young people have no access to health workers.

Children and youth are growing up in an increasingly digital world and are the largest demographic using digital technologies. Not only will they experience the highest rate of digital transformation across the globe, but they are also most likely to experience the greatest impacts of digital transformations with respect to their health and wellbeing. The Commission’s work acknowledges, and in some ways addresses, other age demographics, but believes it is important to understand digital transformations from the perspectives of children and youth. The Commission paid special attention to children and young people, convinced that maximising their safety, wellbeing, and rights in an age of digital transformations represents a litmus test for the whole of society and its concern for the most vulnerable.

More concretely, digital transformations present specific opportunities and threats for the health and wellbeing of children and youth. For example, digital technologies and the data they generate offer enormous potential for improving adolescent wellbeing through increasing adolescents’ access to services and information as well as creating new opportunities for communication, learning, self-expression, and civic participation. However, poorly designed and governed digital tools can undermine the rights of children and youth, exposing them to multiple forms of exploitation and harm (e.g. self-harm, addiction, online bullying and harassment).

Digital technologies are already driving health transformations both directly (through its application in health systems, health care, and self-monitoring of health status and behaviours) and indirectly (through its influence on the social, commercial, and environmental determinants of health). Moreover, due to the influence that dynamics of digital access and literacy might have on health and wellbeing outcomes, we can consider the digital ecosystem itself as an increasingly important determinant of health.

The reason to explore the digital determinants of health in their own right is not to overshadow existing determinants of health frameworks, but rather, to help policymakers comprehend how these latter determinants uniquely intersect within digital spaces and its governance.

The digital determinants of health can be characterised as: i) the digital technologies (and related factors and processes) that directly impact health, through their application in health systems, healthcare, and self-monitoring of health status and behaviours; ii) the digital technologies (and related factors and processes) that indirectly impact health, through their influence (both positive and negative) on the social, commercial, and environmental determinants of health; and iii) the digital ecosystem itself, including the variable dynamics of digital and data access and literacy and their implications for health equity.

Solidarity—along with equity, human rights, inclusion and democracy—is one of the foundational values that the Commission believes should shape future governance in order to derive the greatest public value from digital transformations. Solidarity should be reflected in all dimensions of digital health including the collection, use and sharing of health data and data for health. A data solidarity approach safeguards individual human rights while simultaneously building a culture of data justice and equity, and ensuring that the value of data is harnessed for public good. The articulation of data solidarity, however, requires a new understanding of how the approaches that have emerged to govern data in our societies can be updated to reflect existing, shared goals for health and wellbeing.

Digital transformations are changing our conventional understanding of the health economy. Within each country, the configuration of the actors involved in the health economy has always varied, depending on the public or private provision of health services. In the new dynamics of the digital health economy, traditional actors—namely governments and private health care providers—remain important but we now see a host of new actors—such as technology, social media, and telecommunications companies—joining the ecosystem who have not previously focused on health.

Digital health governance takes place at global, regional, national, and local levels and from multiple sectors. On a global scale, UN agencies and international organisations provide countries with normative and technical guidance on governance mechanisms which have implications on health and wellbeing. Regionally, political unions such as the African Union and European Union bring together nations around common values to form partnerships and mutually beneficial priorities. Nationally, governments produce strategies on digital transformations in various forms that guide policy and legislation. Local governments produce policies relevant to their needs and create services that align to regional/global objectives with strategic frameworks.

Because of the transnational, multisectoral nature of digital transformations, these scales of governance often intersect. The private sector, which is often more agile in adapting to the pace of digital innovations, plays a large role in influencing the direction of governing digital transformations.

Many global, regional and national frameworks for digital and data governance are emerging. Research by the Commission found that most countries now have a national policy or strategy on digital health. Many countries and regional bodies also have strategies for related governance domains, such as data and information and communication technology, that consider aspects of health (for example, the African Union and European Union have adopted The Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa (2020-2030) and the General Data Protection Regulations). The Commission has developed a database of more than 110 digital health strategies as well as a governance database as open resources.

The Commission’s analysis of digital health strategies, including ten strategies from countries with large youth populations, found that national approaches to digital health are not sufficiently grounded in the foundational entry points espoused by the Commission and are not developed through fully inclusive processes. Furthermore, digital health strategies overlook young people’s specific health needs and unique risks in relation to digital technologies and data. Most strategies do however recognise the need for stronger national-level governance of digital health and data and demonstrate that countries are taking steps to strengthen their policy, legal, and regulatory tools in relation to digital health.

Global guidance on digital health and the development of digital health strategies has been developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Globally, the World Health Organization has published the Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020-2025. Many countries’ digital health strategies are informed by the WHO-ITU eHealth Strategy Toolkit.

The Commission recommends that by 2025, all governments should adopt country-wide strategies to safeguard health and digital rights, including regulatory measures to protect children and young people against online harms, training of offline intermediaries to act as health data stewards, and promotion of strong transparency and accountability requirements for emerging AI and machine learning applications in health. The Commission also recommends that governments should advance public participation in the codesign and implementation of digital health policies.

The Commission also recommends that all national governments should enhance the content and implementation of their digital health strategies, including by making use of a comprehensive digital health readiness assessment framework, such as the one proposed by the Commission, increasing country ownership of digital health strategies through building capacity for digital health governance and leadership, and adopting health data governance frameworks and costed digital health investment roadmaps.